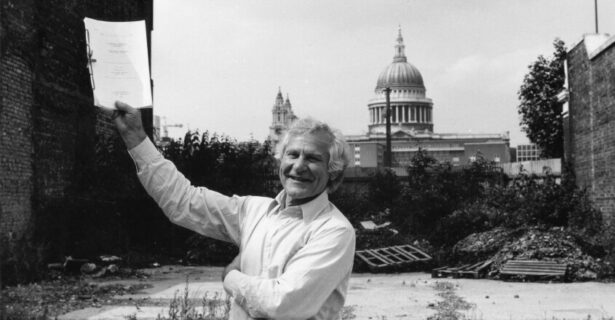

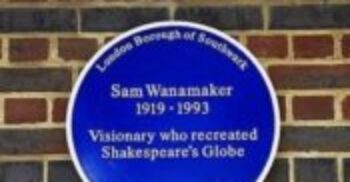

..the right to travel, is not a privilege to be conferred on the few as an act of grace,… it is an attribute of the personal liberty of the citizen which cannot be infringed or limited except by due process of law.Sam Wanamaker - Affidavit, 1957

You’ll put down strangers,

Kill them, cut their throats, possess their houses,

…alas, alas, say now the King,

As he is clement if th’offender mourn,

Should so much come too short of your great trespass

As but to banish you: whither would you go?

What country, by the nature of your error,

Should give you harbour? Go you to France or Flanders,

To any German province, Spain or Portugal,

Nay, anywhere that not adheres to England,

Why, you must needs be strangers, would you be pleas’d

To find a nation of such barbarous temper

That breaking out in hideous violence

Would not afford you an abode on earth.

Whet their detested knives against your throats,

Spurn you like dogs, and like as if that God

Owed not nor made not you, not that the elements

Were not all appropriate to your comforts,

But charter’d unto them? What would you think

To be us’d thus? This is the strangers’ case

And this your mountainish inhumanity.

These amazing people” – she says – “have taught me to see them – and the world – in a whole new way… The lives of refugees are actually as Shakespearean as any in our world right now. Of course, there is suffering – But that suffering is bumping up against moments of beauty; hardship keeps company with kindness, love, creativity, play. The deeper truth is that every human experience that we all lay claim to is also happening for refugees. And Shakespeare knew that this is the reality of the human condition – that tragedy and joy can and do live in intimate proximity, cheek by jowlJessica Bauman - April 2018

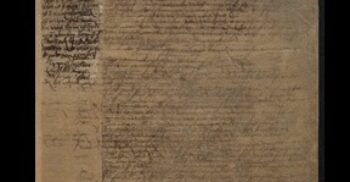

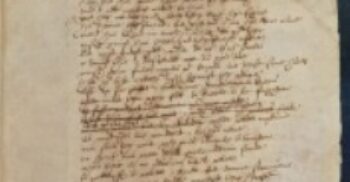

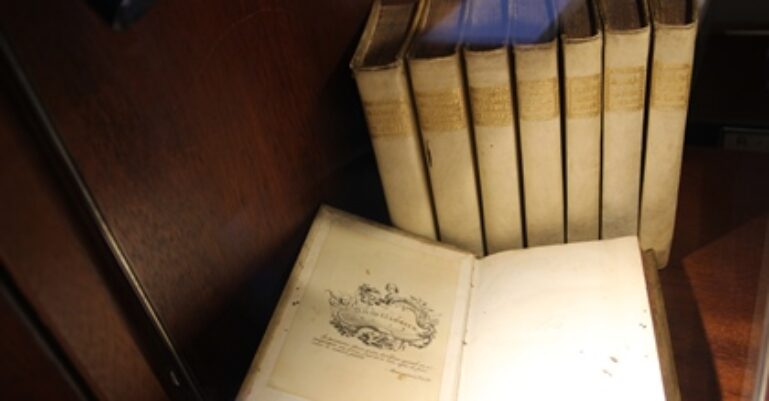

A facsimile of the original folio of Shakespeare’s ‘Strangers’ speech (ff. 8r, 8v and 9r) is on display at the Globe Theatre as part of the Censorship Season and Globe’s Refugee Week in June 2018. The original manuscript is the only surviving example of a script written in Shakespeare’s own hand. It was displayed in two exhibitions during the Shakespeare anniversary year but it is now enjoying a restful sleep, away from light exposure, at the Medieval & Early Modern Manuscripts, Western Heritage section of the British Library.

A Turning the Pages (digital) version may soon be available for visitors to view in the BL’s Treasures Gallery, although there is no definite date for this yet.

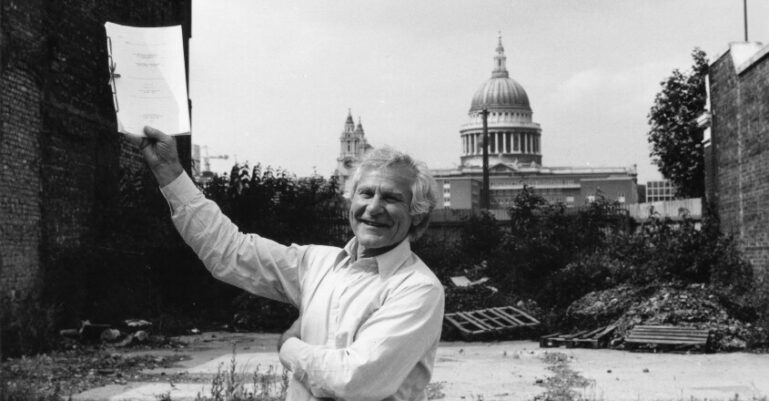

A copy of Sam Wanamaker’s 1957 Affidavit is available to view at Shakespeare’s Globe Library & Archive’

Jessica Bauman is on the ‘Whither Would You Go?’ panel discussion at Shakespeare’s Globe, on 23 June 2018.

Further information on Bauman’s ‘Arden/Everywhere: The “As You Like It Project”:

Gallery

What connects our members’ collections? Here we put a spotlight on some of the curious themes that tie us together.