For many of the 40 or so delegates at APAC’s study day on 17 September 2014, it was their first visit to the Cinema Museum in Kennington, London, but unlikely to be their last. An incredible Aladdin’s cave of memorabilia welcomed us, evoking the cinema-going experience of 1930s, ’40s and ’50s Britain. It set a tone of awe and joy that continued throughout a stimulating day of five presentations and a tour. Funded by a Subject Specialist Network grant from Arts Council England, the Performance on Film Study Day opened with an introduction and welcome from APAC Co-Chair Karin Brown.

Bryony Dixon, Curator of Silent Film, British Film Institute: ‘The Stage and Early Film’

Established in 1933, the British Film Institute is the country’s national archive of film. Holdings include films, posters, stills, and designs, primarily but not exclusively of British film. In her presentation, Bryony Dixon screened a series of (digitised) short, early silent films, dating from 1896 to 1902. She explained that nearly all films of this time were made in and around London because it was necessary to be in close proximity to theatres in order to borrow sets and kit from them. Filming always took place outside to allow enough light for a good picture.

We enjoyed 1896 footage of Leicester Square, where the Lumiere Cinematograph had just arrived. It was common to entice an audience with the promise of filming them as they entered the theatre, and then to screen that footage back to them in the auditorium. Dixon showed the earliest surviving footage of a Dickens adaptation from 1901 entitled Man Meets Ragged Boy, which has been identified as Jo, the crossing sweeper, from Bleak House. We then watched the dramatic The Bandits from 1902, featuring horses, cascading water, and a collapsing bridge – unusually, filmed inside.

Dixon then screened a selection of slightly longer films that were excellent examples of film adopting theatre practice in terms of staging and casting. These included fascinating footage of Herbert Beerbohm Tree in Trilby (1914) and The Talisman (1907), which employed all known examples of stage traps with amusing regularity.

Access to the BFI’s collection is now available through a number of channels, including Mediatheques around the country, YouTube, Screenonline, and the BFI Player. In 2011, a catalogue listing of performing arts films held by the BFI, Arts Council England, LUX, and Central St Martins’ British Artists Film & Video Study Collection was created. This 700-page resource covers material relating to theatre, dance, music, performance art, politics, and poetry, from the 1890s to the 2000s. It is available on the BFI website.

Jane Pritchard, Curator of Dance, V&A: ‘Dance on Film in the Silent Era’

Jane Pritchard explained how film was invented to portray movement, and so dance was the favoured art form to capture during the silent era as it revealed the potential of the medium. Serpentine dances were a popular subject due to the almost continual movement, magnified by the flowing fabric of the costume.

At the 1900 Paris Exposition, the Photo-Cinema-Theatre was a popular attraction, showcasing films of a range of theatre artists. Many dancers featured, including ballet dancers Carlotta Zambelli and Cleo de Merode, and music hall performer Little Tich in his comic dance Big Boots. We watched a digitised selection of these remarkable, hand-tinted films, which provide great insight into dance technique of the period.

Pritchard told how Alexander Shiraev, principal dancer of the Imperial Ballet in St Petersburg, had a studio at the top of the Maryinsky for film and photography. He recorded Le Corsaire, featuring his wife Natalia Matveeva. It had disappeared from the ballet repertoire, but the Bolshoi has now restored the ballet, purely as a result of Shiraev’s film being discovered.

The earliest footage of a British production of ballet on stage is Robert Paul’s 1899 film of divertissements at Crystal Palace. As we watched this illuminating record, Pritchard pointed out the national character dances shown and how the style of choreography favoured manipulation of groups on stage. She followed this with footage of the spectacular Excelsior by Luigi Manzotti from 1913. This vast ‘ballo grande’ was performed throughout the world, with the flag worn by the dancer representing ‘civilisation’ changing to match the country. Unfortunately, only a quarter of the hour-long film survives.

Pritchard discussed why so little film footage of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes exists, suggesting that to Diaghilev, a lack of sound and colour would render it ‘half a production.’ She described three occasions on which the company was almost officially filmed, but sadly the opportunities were lost.

Film served to support dancers’ developing careers, Pritchard said. Anna Pavlova appeared in The Dumb Girl of Portici in 1916, using the fees to keep her ballet company running during the war years. Mixed programmes of film and theatre provided increased opportunities for dancers to work: the Brighton Palladium and the Royal Opera House are known to have shown films, supported by interludes of live dancing.

Martin Humphries, Curator, Cinema Museum: Tour

We were treated to a tour of the host venue, the Cinema Museum, by curator Martin Humphries, who revealed that the history of the building was as captivating as the collections in it. The original museum was created in 1984 by Humphries and Ronald Grant, who had amassed a sizeable collection of cinema interiors and projection equipment by personally stripping out closing-down cinemas. This was augmented by an important acquisition of 3D material from an independent cinema company.

In 1998, they moved to their current premises in Kennington, due to a special connection. The Grade II listed building was originally the Master’s House of the old Lambeth workhouse and became the residence of Hannah Chaplin, mother of Charlie. Charlie Chaplin is known to have stayed at the workhouse for a number of months and writes in his autobiography about visiting his mother there.

The collections of the Cinema Museum now comprise cinema interiors, projection equipment, a library of books and film periodicals, photographs, minute books, stills and film posters. The museum is the official archive for the Brixton Ritzy.

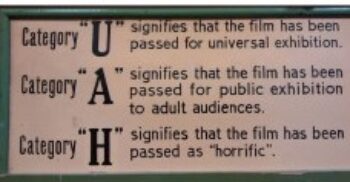

The tour commenced from the grand main hall in which most of the day’s proceedings took place. A wonderful space, it felt both vast and intimate at the same time. Windows were blacked out to optimise film screening, while the brick walls were adorned with signage from the collections. Rows of huge projectors lined the walls. As we toured the rest of the building, we found every possible space occupied by the collections – projectors on landings, cabinets crammed with artefacts, and mounted signage and posters from floor to ceiling. The effect is incredibly immersive and makes the museum a real delight to explore. Highlights included a sign explaining film certificates, which included ‘H’ for ‘Horrific,’ and the stacks of storage boxes for Mitchell and Kenyon’s wonderful films of Edwardian everyday life, each hand-painted with a concise title such as ‘Pigs,’ ‘Rivals,’ and ‘Snowman.’

Lynne Wake and Christopher Bird, Film-makers: ‘Bringing the Archive to Life’

Lynne Wake and Christopher Bird discussed how they have used archival film footage within major dance documentaries. Wake acknowledged the difficulty of using archival film because it requires obsolete equipment to view it. She recommended acquiring vintage equipment to allow flexibility of viewing and using such film, which is the route she and her collaborator have taken.

It was wonderful to see film of a serpentine dance, which had been discussed by other speakers earlier in the day. The 9.5mm film was screened using a restored projector from 1922. Despite a warning of possible technical hitches, the screening was seamless. The flowing, fluid dancing was accompanied by the whirring and ticking of the projector, resulting in quite a hypnotic experience.

This was followed by two fascinating films from the Paris Opera Ballet: A Slow Motion Picture of Dancing and footage from a class at the Paris Opera Ballet School. These 16mm films were shown on a projector from the 1980s. The majority of archival dance film is of this format, which is easy to work with, Wake said.

We were then given a glimpse into Wake and Bird’s working process, as they showed an original extract of the majestic Beryl Grey dancing in Swan Lake in 1952. They subsequently screened part of their own film on ballet in World War II, Dancing in the Dark, into which they had interspersed the original footage, along with sound, to fantastic effect, powerfully illustrating an interview with Grey.

The Edmee Wood collection is a large number of dance films spanning 1958-1972, including some ‘lost ballets’. They were generally made from single stationary cameras and are quite poor quality. Wake and Brid screened two versions of The Royal Ballet’s Ballet Imperial from 1962 to illustrate how transferring the footage to a new format can greatly improve the discernible detail.

We enjoyed a remarkable piece of film from the Nadia Nerina collection. Nerina rehearses the principal role of the ballet Sylvia on the Covent Garden stage. At the side of the stage, also practicing the part, is Margot Fonteyn. The footage therefore allows a direct comparison between the two dancers and their interpretation of the role.

Arike Oke, Archivist, Rambert: ‘Digitising the Archive’

Arike Oke’s presentation examined a recent project to digitise Rambert’s video collection, which includes both performance and rehearsal footage. Oke recruited a member of staff to act as co-ordinator and 16 volunteers for the six-month project. The job of the volunteers was to view all the videotapes within the collection in order to identify the content of the footage. The volunteers were mostly ‘supporters’ and ‘friends’ of Rambert, and so brought knowledge of the company and its repertoire. They worked in pairs and completed a form that prompted them on the elements to record, such as duration, notable dancers, quality of footage, etc.

The decision was made to digitise the videotapes so as to be able to migrate the data to the next suitable preservation format in the future. The material was digitised in different sized files for different purposes: compressed files for viewing and streaming, medium-sized files of broadcast quality, and the large master files containing the original data.

BBC Studios and Post-Production undertook the digitisation for Rambert, following a call to tender. They used a 48 terabyte NAS drive, backed up on to LT05 files and metadata 5 files. Oke said of all the companies she spoke to, BBC S&PP best seemed to appreciate and understand her specific needs, namely not to lose any original data during the transfer process.

Since the project, members of Rambert staff have been using software, originally created for Scottish Ballet, which allows them to view the film collection at their desks. This is a fantastic means by which to allow and promote access within organisations. To illustrate the benefits of the project, and the footage that has come to light, Oke showed an extract of a wonderful film in which Marie Rambert explains the benefit to her dancers of drinking milk.

Anna Landreth-Strong, Curator, Modern & Contemporary Performance, V&A: ‘The Archive of Tomorrow’

Anna Landreth-Strong addressed current exciting developments in the recording and broadcasting of live theatre. In 2009, the first NT Live performance was broadcast – Phèdre, starring Helen Mirren, live from the National Theatre, relayed to cinemas across the UK and around the world. Over the past five years, the popularity of live relay has soared. Studies have found that cinema-goers claim live relays make them more likely to visit a theatre in person, supporting the suggestion that live relays complement, rather than replace, theatre-going.

Landreth-Strong acknowledged the repercussions of ‘event cinema’ for regional theatres because broadcasting is all in one direction – from London. Regional theatres do not currently enjoy this platform, and so may suffer as a result, due to the imbalance in publicity, or audiences going to live relays from London theatres rather than attending live theatre locally.

Despite such reservations, simulcasting is the fastest growing use of digital in the cultural sector. Landreth-Strong provided some facts: 560 out of 700 UK cinemas are screening live performances. The genre has its own industry award, which was last won jointly by the National Theatre and The Royal Ballet. The current Royal Opera House season includes 15 live broadcasts.

She also gave an interesting example indicating a real cultural shift is taking place. St James Theatre in London, newly built on the site of the old Westminster Theatre, included live broadcast in the building plans. The theatre layout preserves film sightlines and has removable seats to make space for cameras and equipment. This popular format looks set to expand and develop, changing both the way we consume theatre, and how we record it.

Anna Fineman is Assistant Curator of the White Lodge Museum at the Royal Ballet School, Richmond Park.

Gallery

What connects our members’ collections? Here we put a spotlight on some of the curious themes that tie us together.